Reading Time: < 5 min

In August 1988, the renowned Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted a groundbreaking exhibition titled “Deconstructivist Architecture,” masterfully curated by two of contemporary architecture’s leading figures, Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley. This landmark event showcased the daring works of seven emerging architects, including Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Wolf Prix, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, Daniel Libeskind, and Bernard Tschumi.

The exhibition sparked a lively architectural debate, heralding the dawn of a new era in architecture. Characterized by a dynamic, fragmented vision and a decisive opposition to classical order, this architectural movement opened new creative horizons. Many of the featured architects, including Hadid and Koolhaas, delved into studies on Russian Constructivism, while Eisenman collaborated with the philosopher of deconstruction, Jacques Derrida, further intensifying the ambiguity of the discourse.

Although the term “Deconstructivism” was initially unfamiliar to all participants, it gradually gained significance over the years, catalyzing a proliferation of architectural works aligned with this style. This phenomenon was facilitated by the rapid changes in the global context, such as the opening of nations like Poland and Russia, and by world-shaping events like the fall of the Berlin Wall and the tensions between the United States and Iraq.

In this context of tumultuous change, Daniel Libeskind emerges as a revolutionary architect, shaped by a multicultural and multidisciplinary background. Born in 1946 in post-war Poland to parents who survived the concentration camps, Libeskind began his musical studies in Israel before immersing himself in architecture at the prestigious Cooper Union in New York, where he crossed paths with Peter Eisenman. His early works, influenced by his experiences in Milan, Como, New York, and London, define him as an eccentric experimenter of the 1980s. Libeskind is noted for his bold, central experimentation, creating grand abstract machines that echo the philosophical reflections of Deleuze, where thought offers a new way to see and understand architecture, challenging traditional ideas of unity and totality and proposing instead a vision of architecture as a process of becoming and difference.

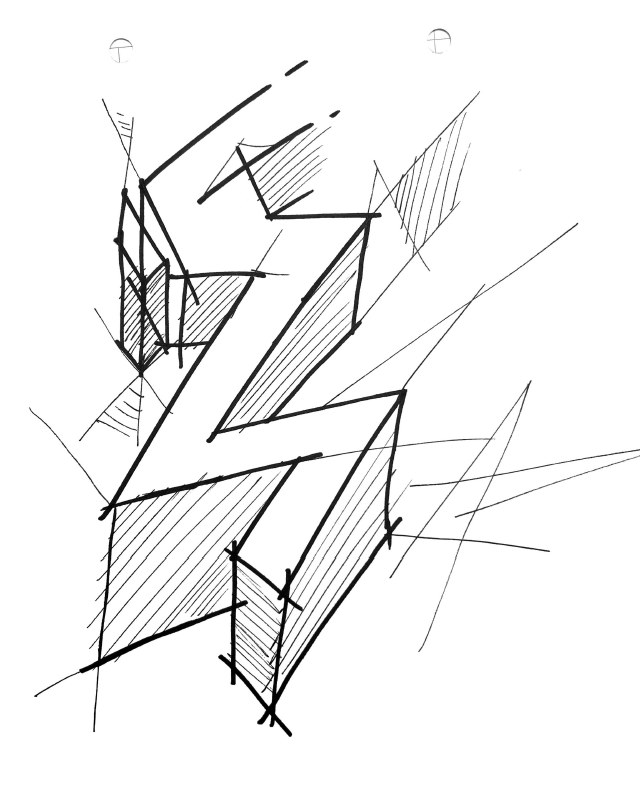

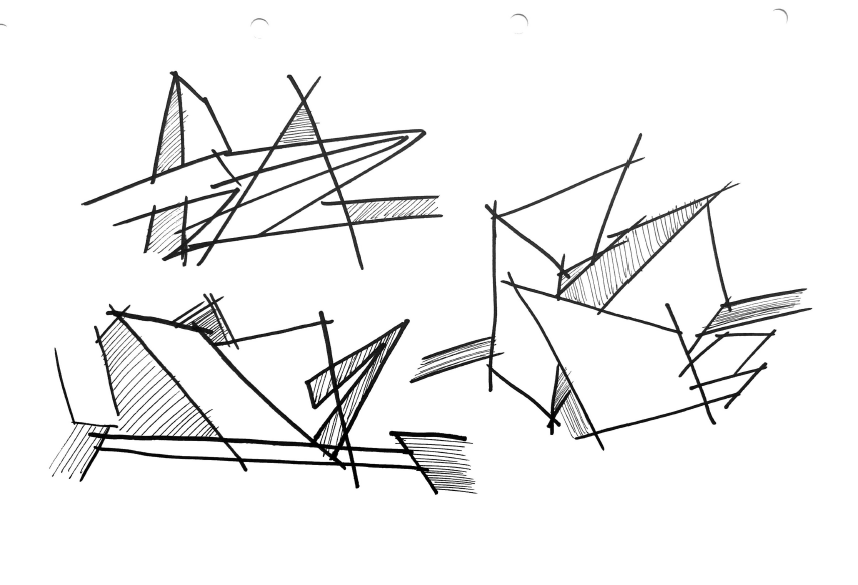

These devices present themselves as abstract machines with designs reminiscent of musical scores, challenging traditional canons. In Italy, these visions were presented by Aldo Rossi, but they were understood by few and recognized by even fewer as the future ideas of new architecture. Libeskind’s experimentation culminated in Berlin, a city embodying both rupture and vitality. In 1987, he created City Edge, a multifunctional building that intertwines forms and layers functions, offering an original interpretation of the concept of stratification. In this context, the layer takes on a dramatic force, presenting the drama of a world that cannot be recomposed.

Libeskind’s masterpiece is the new wing of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, a work that unveils an unprecedented architectural conception. The building unfolds as a jagged, oblique line—a novel and dynamic interpretation of the traditional museum. The building’s sharp lines and fractured forms create a labyrinthine and dizzying experience for visitors, opening new possibilities and challenges. With the museum, Libeskind transcends mere architectural communication, introducing deep and complex symbolism. The building is not a standard box for mass consumption but a testament to architecture that challenges and ushers in a new era. Libeskind, with his innovative vision, stands out as an architect who confronts drama, communicating through intricate symbolism and forms that reveal the fragmentation and complexity of the contemporary world.